| english | español | français | italiano

We interviewed Pierpaolo Leonardi on the trajectory of USB, and in general of conflictual unionism, from the preparation of the general strike of 11 October to the mobilisations for No Draghi Day on 4 December, and on the situation of class conflict to come.

Interview with Pierpaolo Leonardi, USB National Confederal Executive

Question – In mid-July, grassroots and conflict unionism in Italy managed to converge on 18 October as the date for the general strike against the policies of the Draghi government, which was then brought forward to 11 October. The numbers of strikers, the number of city mobilisations and their participation seem to have proved the organisers of 11 October right. How do you assess that day and its consequences, in the light of the certainly not easy premises, in which the enchantment of the current executive is broken for the first time?

Answer – The need to start the confrontation with the varied and composite world of grassroots unionism was born from the murder of comrade Adil, logistics delegate of Sicobas, coldly murdered during a picket. An event that retraced the story of the murder of our logistics delegate Abdel, also during a picket line in Piacenza, a few years earlier.

USB decided, together with Sicobas, to call an immediate general strike in the entire logistics sector in protest at yet another murder of union delegates, and from there developed the path that led to the strike of 11 October

There was already a political arena in which a part of grassroots unionism had been confronted for more than a few years, in which USB had never participated, and which in past years had proclaimed general strikes that in reality had gathered little support, in which Sicobas also participated. It was a place where a rather strong antagonism towards us had developed, because we had repeatedly argued that the time of the grassroots union form was over and that it was necessary to work on the construction of the confederal, class and mass union.

However, our decision to contribute to building the strike for the death of Adil, which Sicobas had of course immediately proclaimed, allowed the resumption of the confrontation that had been interrupted for years and which, on the initiative of USB, broadened participation to other trade union organisations that had always been outside the pre-existing circuit.

This enlargement, the awareness that the situation needed the broadest possible response, the dramatic context of the pandemic and the determination of the class enemy to use it to strengthen its command over society and in particular the world of work, led everyone to find, not without effort, a common ground for initiative which then produced the general strike of 11 October.

The political success of the general strike, which became a moment of attraction and participation even for a very wide range of political forces that had long lacked a mass initiative in the social and trade union spheres, was realised with the participation of tens of thousands of people in the local demonstrations and national events strongly desired by the USB

These took place in front of the Ministry of Education, Brunetta’s Ministry of Civil Service, and the MISE: symbolic places identified as the three main points of conflict in the violent productive and social reorganisation supported by the Draghi government and Bonomi’s Confindustria.

The very high number of participants, which we estimate at around one million, was indeed an important signal that led us not to exhaust the confrontation with the other organisations but to maintain it while respecting the different identities.

Question: In the weeks following the 11 October strike, there was a desire on the part of the government to restrict the margins of action on the streets in general, an attempt of which the Union of Basic Trade Unions was also a victim, reacting to the attempts to ‘put a gag order’ on what was emerging as social opposition to the Draghi government. Can you describe the situation of this umpteenth “authoritarian twist”?

Response – The general strike of the 11th has certainly helped to revive the struggles. The cessation of street initiatives imposed by the pandemic had made it very difficult to forcefully express opposition to the political choices of the Draghi government and the European Union, which have tried in every way to use the pandemic for a gigantic redefinition and relaunch of the interests of the bourgeoisie and national and European capital.

The great success of 11 October and the demonstrations of that day certainly represented not only a response and the proposition of an overall platform of struggle, but also an important moment of resumption of the word of the conflict. This immediately led to countermeasures by the repressive apparatus, which tried in every way to prevent the movement that had been created from developing and growing.

Even using the excuse of the ‘no vax’ demonstrations, it imposed truly unacceptable restrictions on demonstrations, marches and mobilisations of any kind. On several occasions we have had to clash heavily with the prefectures and police headquarters in order to maintain democratic rights and the right to strike, which had already been heavily attacked in previous years and even more so during the pandemic.

It should be remembered that our general strike in March 2020, which was symbolically called in the health sector and lasted just one minute, cost us more than €5,000 in penalties from the Strike Committee!

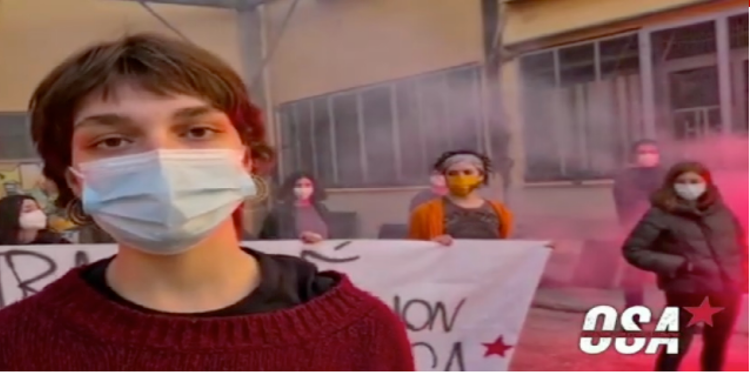

Question – In the spirit of the general call for a united strike on 11 October, the confrontation between the various conflicting trade union organisations led to the proclamation of a ‘No Draghi Day’ for Saturday 4 December. This day was articulated with various local demonstrations that saw the participation and active support of political forces – such as Potere al Popolo – and youth organisations, such as OSA and Cambiare Rotta. Can you take stock of this day from the USB point of view?

Response – The success of the general strike of 11 October, the mass response that it had and the simultaneous acceleration by the government of the restructuring processes preparatory to the use of Recovery Fund funds in full support of enterprises, the resumption of mass layoffs, the spread of precariousness, the attack on citizenship income, the new violent attack on pensions and the disappearance of the minimum wage from the political scene have imposed a mass response that has seen all the conflicting trade union organisations, already promoters of the general strike, give life to the No Draghi Day involving a large part of the political forces of the alternative left.

On that day, 29 Italian squares were filled with marches and demonstrations, which broke the spell of unanimity surrounding the former governor of Bankitalia and then of the European Central Bank. The attempt by almost all the political forces, including President Mattarella, to make Draghi look like the only one who could save the country and therefore he should be supported in all his decisions, even if taken without any parliamentary passage and with the government of all completely subjugated by Draghi’s little team, has finally found a response of struggle and mobilisation that will have to continue in the coming months to prevent his election as head of state and to oust him as president of the council of ministers.

I want to underline the widespread and truly mass presence of young people and students at the demonstrations all over Italy, and in particular of average students organised in OSA, which then gave rise to a season of school occupations that is still going on despite brutal and unjustifiable repression

Question: The will to fight expressed by the conflictual trade unions has been matched by an attitude substantially subordinated to the policies of the current executive by the CGIL, CISL and UIL, from which the CGIL and UIL, which have called for a strike on 16 December, have not ‘broken away’. What was their role and what are the tasks of trade unionism in conflict?

Answer: The capacity for continuous and articulated mobilisation of the forces of conflict, of grassroots and class unionism and of the antagonistic political forces has been counterbalanced by the deafening silence of the unions, accomplices and accomplices of the restructuring processes, from the recommendations to the bosses to lay off workers sparingly, to listening to the sirens of Bonomi and Draghi, to hoping for a new social pact that would guarantee social and productive reorganisation from any organised conflict.

Draghi’s pats on the back to Landini in front of the CGIL headquarters, attacked by fascists and not defended by the police, are an indelible image of this.

The strike of 16 December is really a dutiful satisfaction for a base increasingly astonished at the complicit attitude of its leaders and a signal to Draghi that his absolute willingness to pay is reciprocated by the respect of the commitments made to guarantee their greater function and role in the country.

We are therefore only at the beginning of a long-lasting battle and of strong mobilisations that, despite the resurgent pandemic and the immoderate use in a repressive function of those who take to the streets to protect a misunderstood individual freedom, is already identifying new areas of struggle and organisation.